Lake Michigan is now recognized as a premier freshwater fishing spot. The lake was teeming with trout kinds and native fish kinds in the early days of the United States, and they would seem to never be able to catch them all.

Management programs had to introduce new species and attempt to give native fish a chance to reclaim their habitat between those periods as the lake’s ecology deteriorated.

Whether you’re a lover of learning about Lake Michigan’s ecological history or are a seasoned fisherman, this piece covering twenty of the most significant fish is sure to interest you.

Whether you’re an avid angler or want to learn about Lake Michigan’s ecological history, this article about twenty of the most important fish is sure to appeal to you.

20 Most Common Fish in Lake Michigan

1. Chinook Salmon

Beginning in 1877, chinook salmon, commonly known as king salmon, were brought to the Great Lakes, and by 1967 they had become a native species. They were transported to Lake Michigan as part of a biodiversity restoration effort.

Salmon grow to be between 20 and 35 inches (51 and 89 cm) long, and may weigh up to 35 pounds (16 kg). In Lake Michigan, a 43-pound (19.5 kg) fish was caught in Wisconsin. Silver sides, a white belly, and a blue to blue-green iridescent stripe on their backs are common characteristics. The black gums and mouths of these salmon distinguish them from other salmon.

For reproduction, Lake Michigan king salmon must migrate between the two oceans. Wildlife agencies, on the other hand, replenish their populations every year via restocking. I’ll go over how to do it later.

2. Coho Salmon

Another salmon species introduced to the Great Lakes at the same time as king salmon is coho salmon.

Coho salmon may reach a maximum length of 26 inches (66 cm) and weigh up to 12 pounds (5.4 kg). You may identify coho salmon apart by their white gums, somewhat forked tail, and 12-15 rays in their anal fin, which are similar to those of king salmon.

The Pacific Ocean is also home to coho salmon. They, too, are constantly replenished in the lake by hatchery operations, similar to king salmon, as they struggle with effective reproduction in their lake habitat.

Just a few bigger fish, people, and lampreys have been known to feed on adults, which have few natural predators. Coho salmon spend most of their lives in the open parts of the lake, moving into streams and shallower parts of their origin in the autumn.

3. Steelhead

Steelheads are the kind that is native to coastal saltwater environments, whereas rainbow trout is essentially the same species. Lake Michigan, which serves as the species’s ocean habitat, is where the species is stocked. They return out into the lake after reproducing in the streams and tributaries of the lakes.

Lake Michigan’s three steelhead populations typically grow to lengths of 30 inches (76.2 cm) and weigh up to 12 pounds (5.4 kg). With a white belly, silver sides, and a green back, steelheads resemble salmon in appearance. They have a distinct radiating pattern of spots on their tails, as well as a purely white mouth.

The species spends the majority of its time in coastal, saltwater environments around the Western United States. Unlike salmon species, they do not perish after reproducing. Steelheads return to the sea after laying eggs in freshwater, but just a few of them reproduce multiple times throughout their life cycle.

When the weather cools down, adults head towards streams, away from their open-water hunting grounds. After four to five years of age, steelheads typically spawn.

4. Rainbow Trout

Rainbow trout may be found in Lake Michigan, just like their close cousins the steelhead. Rainbow trout are a naturally occurring kind of trout that lives its entire life in freshwater.

The size and color of the two species may be used to differentiate them. In lakes, rainbow trout may reach a maximum size of 20 pounds (9 kg), whereas in rivers, they grow to only 5 pounds (2 kg). They are lighter in color than steelheads and lack the lustrous sheen of steelheads. They have fewer bright spots.

Rainbow trout and steelheads are difficult to distinguish from one another because they live in the same environment and have identical characteristics. The strains’ origin is the most significant distinction between them in Lake Michigan.

5. Brown Trout

Around the 1800s, brown trout from Europe and Western Asia were introduced to North America. From Canada and the eastern United States to the West Coast, they can now be found throughout the continent.

Silver-colored with an X-shaped band on their back, white lips, spots all over their bodies, and a square tail, brown trout in Lake Michigan are most often found. They turn reddish-brown with brighter red or black markings while spawning, then return to their original color.

The average brown trout is around 16 to 30 inches (40 to 76 cm) long and weighs about 16 pounds (7.2 kg). Approximately one million trout are introduced into Lake Michigan every year, as with other trout species.

They’re usually found 2-5 miles (3-8 kilometers) offshore in water 15-70 feet (4.5-21 meters) deep throughout the majority of the day. Most fish are captured while trolling lures at their optimum depths, and they’re called as skittish fish that will scare easily.

6. Brook Trout

Brook trout may be found in Lake Michigan’s shorelines, as well as in streams and tributaries around the lake, and are native trout species.

Brook trout grow to be about 4 pounds (1.8 kg) in size on average and grow to be around 10-20 inches (25-51 cm). Their backs are black or brown, with crimson dots surrounded by blue halos and crimson fins on their undersides.

7. Lake Trout

Lake trout were formerly one of Lake Michigan’s most common fish, but by 1956, they had practically vanished. The Great Lakes Recovery Program, which included a variety of fish species and aimed to repopulate missing native species, was inspired by their disappearance.

Lake trout reach lengths of 17 to 36 inches (43 to 91 cm) and can weigh up to 30 pounds (13 kg). The color ranges from pale green or grey to black. The backs and sides of the majority of individuals are covered in light spots with worm-shaped patterns.

Almost a million lake trout are introduced into Lake Michigan each year, despite their native status. Since the species has not yet been able to re-establish itself in a way that permits it to reproduce consistently, it cannot do so. The majority of lake trout spend their lives in water depths above 80 feet (25 meters).

8. Largemouth Bass

Largemouth bass may be found in Lake Michigan’s depths around all types of underwater structures, making them the largest member of the sunfish family.

Their backs are green or dark, and their sides and bellies are greenish or yellow. The largemouth’s upper jaw is farther back on the face than the smallmouth bass’s, and the largemouth has a bigger mouth.

Largemouth bass grow to be between 6 and 16 inches (15 and 40 cm) long and may weigh up to 7 pounds (3.1 kg). They school with up to five individuals and are seldom found in water deeper than 20 feet (6 meters). They usually lurk behind sunken logs, lily pads, and rocky outcrops and mounts. They migrate to colder waters during the winter.

Muskellunge, walleye, northern pike, and perch are predators that feed on young bass. They feed on invertebrates, insects, and amphibians as well as smaller fish such as minnows and shad.

The fact that muskies are difficult to hook is the primary reason they are considered difficult to catch. They have plate lips that make it difficult to catch onto hooks and are tough to trick because of how difficult they are to catch onto.

Muskies are known as “the fish of a thousand casts” in sportfishing circles because to their amazing eyesight and difficulty to hook. Ambush predators lie in wait on grass mats and spring out at Passing prey animals.

9. Walleye

The distinct eyes of walleye have a film over them that gives them the glassy-eyed appearance, and they get their name from there. When walleye are most active at night, this film helps them see better in low-light situations and hunt.

Walleye, a bigger species of perch, are mostly silver in color. They can reach weights of 10 – 20 pounds (4.5 – 9 kilograms) and grow to lengths of 2.5 to 3 feet (0.75 to 0.9 meters).

They may be found all around Lake Michigan, preferring the depths during chilly weather. Walleye will readily strike spoons and other lures that resemble the smaller fish they prefer to eat, making them a popular ice-fishing target.

10. Northern Pike

A gluttonous native species in Lake Michigan is related to the musky, northern pike. Overfishing and invasive species have decimated their populations, as has happened to other species, but rehabilitation efforts have shown to boost them.

The duckbill-shaped mouth, streamlined body, and sharp cone-shaped teeth of northern Pike make it one of the fastest-swimming fish in the lake. Their cheeks are covered in scales, their lighter markings resemble beans, and rounded fins distinguish them from muskies.

Most northern pikers are roughly 10-20 inches (25-50 cm) long and weigh about 4 pounds (1.8 kg), although some may grow up to 37 inches in length. In warmer weather, they prefer shallower water and are most often seen in grass beds. They swim towards the lake’s bottom when it gets chilly. They seek out colder water.

From shrews to frogs to smaller fish to other pikes, northern pike devour everything they can swallow. Choking on a prey item too large for them to consume has even been known to kill them.

11. Muskellunge

Muskellunge, also known as muskies, is one of the world’s most difficult freshwater fish to catch. They can grow up to 44 inches (112 cm) long and weigh up to 50 pounds (22.6 kg).

Muskies and pikes have similar body shapes, with sleek tubes and vicious teeth and pointed jaws. The tiger-stripe sides, pointed fins, and half-scaled cheeks distinguish a musky from a northern pike.

In most northern freshwater ecosystems, muskies are the dominant predator. They consume fish, birds, small mammals, and amphibians in the form of anything they can swallow or rip apart on a strike.

12. Lake Sturgeon

True living fossils like sturgeon may be found in Lake Michigan’s lake sturgeon. Since taking the world stage more than 100 million years ago, these fish have barely changed. Sturgeon have a long life expectancy and a sluggish development rate, with specimens exceeding 70 inches (177 cm) and weighing more than 200 pounds (90 kg).

Several characteristics that other fish have evolved from are still present in Sturgeon. They resemble sharks in appearance, having a heavy torpedo-shaped body with bony plates. The undersides of most lake sturgeon are white, and their backs are black, gray, or greenish.

On the muddy lake bottom, these bottom-dwelling fish use barbels to detect tiny creatures like invertebrates. They are suction feeders that can only swallow tiny prey things since they have no teeth and small mouths. They spend the majority of their time in less than 30 feet (10 meters) of water, although they may be found in deeper parts of Lake Michigan.

Lake sturgeon, revered by indigenous communities, had robust populations and protection for a long period. Before their value for caviar, meat, and other products were discovered, many contemporary fisherman viewed them as a nuisance fish and killed off much of the population. Sturgeon became a target of severe overfishing once this was known.

13. Yellow Perch

Because of how delicious they are, yellow perch are more often caught by fisherman than other types of fish. The sides of these 7-10 inch (18-25 cm) long fish are yellow, while the back is greenish.

Perch are a common fish found in both shallow and deep water around Lake Michigan. They’re a highly adaptable species that serves as a vital food source for bigger predatory fish.

Minnows make up the majority of a fully grown perch’s diet, which includes insects, larvae, and zooplankton.

Perch are overpopulated in the Great Lakes, unlike some other fish species. Their high reproductive rate, as well as overfishing of predator species, are to blame. The stocking of predatory species like bass, walleye, pike, and salmonids is the most common way to manage yellow perch.

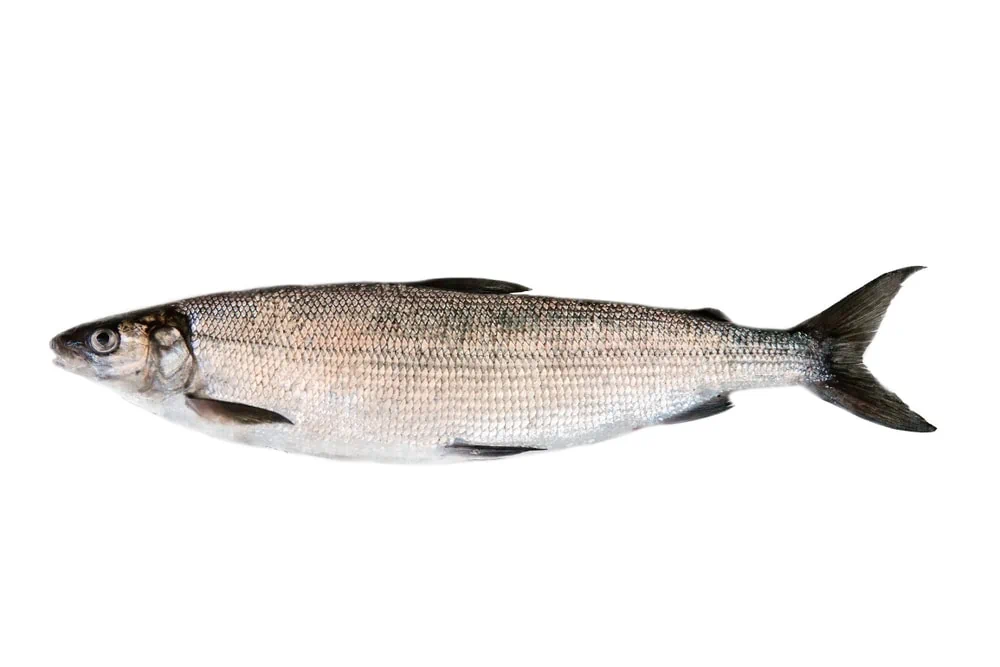

14. Whitefish

The light color of lake whitefish gives them their name. Their size, silver to olive color, and the overhanging nature of their upper jaw distinguish them from one another. Their fins have a darkened edge and their tails have an extreme fork to help them swim faster.

Lake whitefish schools are abundant and prefer to stay at depths of up to 200 feet (61 meters). Whitefish average about 12 inches (30 cm) in length and about 4 pounds (1.8 kg) in weight on average. Despite this, lake whitefish caught by the International Game Fish Association (IGFA) has a weight of 14 pounds (6.3 kg), which is much larger than normal.

Inshore and in shallow water, juvenile whitefish may be found feeding and growing. They travel to the lake’s deepest points and school in enormous numbers once they become adults.

15. Catfish

Channel catfish, flathead catfish, and three types of bullhead catfish are just a few of the numerous species found in Lake Michigan.

The scaleless bodies, long barbels around the mouths, and lack of teeth distinguish catfish from other fish. From a pound or two to as much as 80 pounds (36 kg) in weight, the species found in Lake Michigan vary.

The majority of catfish dwell in holes on the seashore’s bottom and sides. Catfish may be found at almost any depth, but are most common in places where currents drive prey species near them, such as lake mounts, points, and structures. They’re indiscriminate feeders that can consume nearly anything that enters their mouths.

16. Crappie

The bodies of crappies are tall and slender, and the coloration ranges from light to dark.

On their bodies, black crappies have dark irregular marks. They are often found near the beach, hiding in thick vegetation or behind buildings.

The vertical stripes and spots on white crappies’ sides are typically dark. They’re most often seen in open water.

Both species are gregarious and live in large colonies. During the breeding season, they school in large numbers and create closely packed nests that form gigantic nesting colonies. Very tiny fish, zooplankton, crustaceans, and insects make up the majority of a crappie’s diet.

Crappie of either species is only about 12 inches (30 cm) long and weighs about one pound (0.45 kg) on average.

17. Sea Lamprey

All of the Great Lakes are home to sea lampreys, a predatory invasive species that is devastating. Lampreys were able to cross rivers and swim into the Great Lakes, despite being a marine species. They spawn in rivers, like other species do. Lampreys adapted to their habitat and remained after they were captured in the lakes.

The body of a lamprey is eel-like, and its mouth is enormous. A sharp, pointed teeth and a pointed, tough used to slice prey animals are located inside the mouth. Lampreys that are landlocked grow to be about 25 inches long (64 cm).

Lampreys are filter-feeding juveniles that may spend up to ten years burrowing into sediment. Adult lampreys are parasitic throughout their lives. They suck blood from the host by using their mouths to attach to fish or other creatures in the water.

Lampreys are a concern since they kill their host in freshwater habitats. They coexisted with fish in the ocean, and the host rarely perished as a result of them. Even before humans overfished these species in the Great Lakes, they reduced fish populations.

Human ingenuity was the catalyst for sea lampreys to enter the Great Lakes. Before the Welland Canal was built, Niagara Falls was the limit upriver for lampreys; however, now that they have access to the lakes, they can go as far as they want.

Lampreys practically took over Lake Michigan at one time due to their extremely quick reproductive potential. Lampreys were poisoned by pesticides, but not by other aquatic creatures. Every four years or so, these larval and juvenile lampreys are targeted in tributaries around the Great Lakes.

Lamprey populations in all of the Great Lakes have declined as a result of lampricides used in conjunction with traps and barriers along travel routes.

18. Rainbow Smelt

Rainbow smelt is native to the Northern Atlantic Coast, but not Lake Michigan. The fish were introduced into Lake Michigan in 1912, after being introduced into Crystal Lake, Michigan.

Smelt have trout- and salmon-like bodies, although they are significantly smaller. Rainbow smelt have purple, pink, and blue iridescent sides to their long slender bodies. Adults grow to be 3-6 inches (7.5-16 cm) long.

The majority of a rainbow smelt’s diet consists of crustaceans and minnows. In addition, they adore insect larvae, which is the species’ primary bait for hook-and-line fishing. They spend the majority of their time in the middle of the lake, but will descend to the bottom during sunny daylight hours because they are sensitive to light and temperature.

19. Alewife

In North America, alewives are referred to as shad, which is an anadromous species of herring. The Welland Canal was used to introduce them to the Great Lakes, as well as boat ballast tanks by accident.

Alewives are a significant portion of salmon and trout diets for predator species in the Great Lakes and make up an important part of their diets. The average length of a small silver fish is around 10 inches (25 cm), with a chunky body.

Several species in the Great Lakes have been blamed for their decline. This is primarily due to their eating of zooplankton and fish eggs. Seasonal “die-offs,” when enormous groups of alewives die and wash up on beaches, are not uncommon.

20. Round Goby

The invasion of the round goby in the Great Lakes is mostly attributed to shipballast water. This little fish is a plundering eater that can outwit local species for food.

Due to their appetite, round gobies cause the majority of their damage. They eat a lot, to put it simply. The issue is that these fish devour other species’ eggs, putting pressure on their populations. This includes gobies that have evolved to eat by predators.

Outside of chinook salmon, practically every predator fish has learnt to eat round gobies, but this does not appear to help their numbers. Their capacity to outcompete competing species in their specialty, as well as their rapid reproduction, are the main reasons for this. A round goby can produce hundreds of eggs each year during breeding.

A round goby is typically around 10 inches (25 cm) long when fully grown. They have a flattened appearance on their bellies and are generally dark gray or mottled. Gobies may be found at any depth, hunting for food around the lake bed.

The Introduction of Predator Fish Species to Lake Michigan

The Great Lakes were virtually full of invasive fish species by the mid-1950s, and most native fish had gone extinct or had vanished from the lakes. Invasive species like alewives and sea lampreys, as well as overfishing, were among the factors contributing to these issues.

State governments started introducing predators to the Great Lakes in the 1960s. Because they could become a top predator in the lakes and reduce alewife populations, salmon were selected. Along rivers, lampreycides and more effective barriers for invasive species were installed.

The emergence of species has boosted the sportfishing industry and created a new ecological equilibrium among Great Lakes fish species. In the years since, even native species have returned to these introductions, which can be considered successful.

The Great Lakes’ problems have yet to be resolved. In the Great Lakes, lake trout, salmon species, and other fish have had difficulty reproducing. They try to spawn in tributaries, but their efforts are mostly futile.

Let me explain how fish are kept stocked in lakes through wildlife management programs in a very basic way. Nowadays, state programs collect eggs from tributaries, incubate them in hatchery facilities until the juvenile fish are large enough to survive, and release them back into the water. The eggs of these fish are eventually deposited in a tributary, and the cycle repeats itself.

Millions of fish are artifically stocked into the Great Lakes every year in order to maintain population levels. The majority of species are unable to travel across the Great Lakes using conventional paths. While some species, such as lake trout, have had limited success with hatching their eggs, the majority of the fish in the lake are released from government hatcheries.

Yet, despite ongoing attempts, the ecosystem is far from ideal, and the imported and reintroduced fish species have had the chance to adapt and reproduce on their own thanks to previous efforts.

Sportfishing and Why It Matters

Sportfishing and, in general, fishing are often portrayed in a negative light. The bulk of anglers are the ones who follow rules and respect the sport, even if there are a lot of dishonest individuals out there that may do a great deal of harm to an ecosystem.

Commercial fishing, not recreational fishing, is the most harmful to the environment. That isn’t to say that anglers aren’t responsible for the creatures they catch, rather it’s a reality that their impact has less clout than a commercial company.

All of the revenue generated supports native wildlife rather than destroying it, including licenses, fishing gear, boat ramp rentals, and more. Fish stocking, egg and juvenile care, invasive species management, and environmental cleaning are all examples of state-level initiatives that operate across the Great Lakes.

Wildlife management funds are not allocated in most states. License sales, donations, and federal grants are used to fund the entire budget. In Minnesota, you may learn more about how it works.

Hunters and fishers, more than other groups, actively contribute to the conservation of our remaining wild areas, which may surprise a lot of people. This involves voting in favor of higher taxes on specific sales in order for the funds to go directly to wildlife management activities.

The surrounding regions lost a lot of money, jobs, and resources when Lake Michigan’s trout populations declined in the mid-1900s. These were reintroduced as a result of the introduction of fish species like salmon and efforts to restock native species like lake trout.

It also presented a fantastic chance for freshwater sport fisherman. The money is then contributed by those anglers to keep the programs going. These initiatives have breathed fresh life into the Great Lakes, rectified numerous errors caused by human activity, and assisted many cities in the regions at once. While not always effective, they have helped save towns.

I’d encourage individuals who are passionate about protecting our environment to put pressure on government officials and commercial entities to improve their actions. Sportfishing is a major concern, as it conserves resources far more than it causes harm.