Discover fascinating honey bee facts on this page, encompassing various aspects such as the diverse types of honey bees, the intricate life-cycle of these remarkable insects, the captivating life-cycle of a honey bee colony, and the intriguing presence of three distinct types of honey bees within a colony.

Introduction: Unveiling the Honey Bee

Observe honey bees as they gracefully traverse gardens, fields, and parks, diligently gathering nectar and pollen from one flower to another.

Within land-based ecosystems, honey bees, alongside other pollinators, assume a crucial role. This partnership originated during the Cretaceous Period when flowering plants provided bees with nourishing nectar and pollen. In return, these industrious insects disseminated pollen to other blossoms, facilitating plant reproduction and dispersion.

The nectar collected by honey bees is transformed into honey, a sugary substance carefully stored as sustenance. The honey produced by a colony of honey bees serves as an esteemed food source, coveted by various creatures, including humans. Beekeeping, driven by the desire to acquire honey, dates back at least 7,000 years.

Embark on an exploration to unravel more astounding details about these captivating creatures…

A Honey Bee Defined

The Western honey bee, the most prevalent species among honey bees.

Rather than representing a solitary species, any insect within the Apis genus qualifies as a honey bee. (A genus refers to a cluster of interconnected animals.) Presently, seven acknowledged species fall under this genus, collectively recognized as honey bees.

The Western honey bee, scientifically known as Apis mellifera, stands as the most widespread species of honey bee. Beekeepers predominantly rear this particular species.

Approximately 29 subspecies of the Western honey bee have been identified, including the European dark bee and the Italian bee.

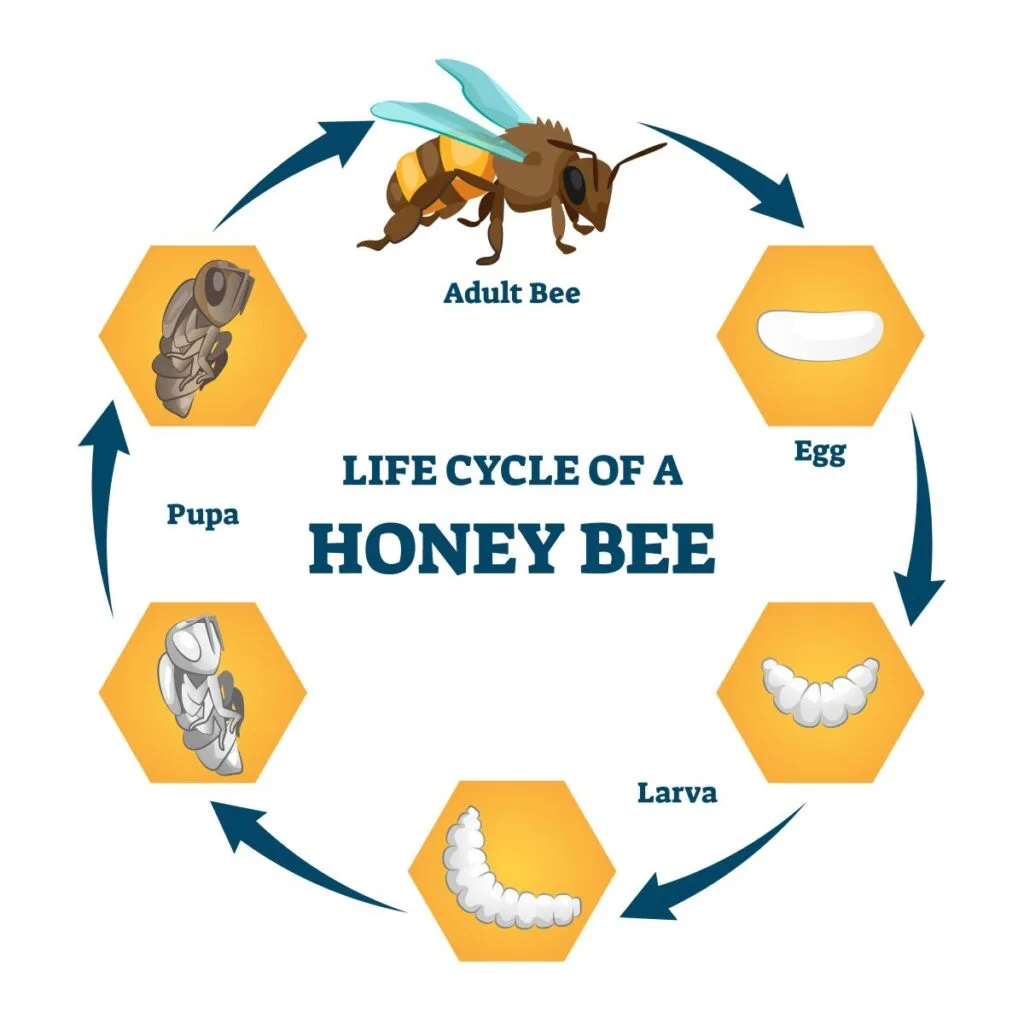

A honey bee undergoes four distinct developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. In their larval phase, honey bees lack appendages and wings, bearing little resemblance to their mature form.

During the pupal stage, honey bees undergo a transformative process termed metamorphosis, which reshapes their bodies from larval to adult form.

Insects in Tandem with Honey Bees

Bumblebees share close kinship with honey bees.

Belonging to the Apidae family, honey bees coexist with their closest relatives. This family encompasses bumblebees, stingless bees, orchid bees, carpenter bees, and cuckoo bees.

Similar to honey bees, certain stingless bees produce honey and are kept by humans for this very purpose.

The Apidae family comprises approximately 5,749 species. (Source)

The Apidae family falls within a broader assemblage of creatures: the Hymenoptera order. This group encompasses sawflies, wasps, ants, and bees.

The Foraging Habits of Honey Bees

Observe honey bees diligently traversing gardens and fields, flitting from one flower to another in their quest for pollen and nectar.

The bees spotted foraging for sustenance primarily comprise worker bees, one of the three bee types within a single colony. Further insights into the different bee types await your exploration below.

Worker bees adeptly collect pollen using specialized structures on their hind legs referred to as “pollen baskets” or corbiculae. Perhaps you’ve observed honey bees returning to their nests with bulging pollen baskets, brimming with vibrant pollen.

Upon returning to the nest, a honey bee conveys information to fellow workers, indicating the locations of food sources through an extraordinary dance known as the “waggle dance.”

In addition to dance, bees employ chemical communication via pheromones. Pheromones released by the queen bee convey her authority to the worker bees.

Worker bees gather nectar, which is subsequently utilized to produce honey. This delectable, energy-rich substance finds its storage within specialized structures within the nest, known as honeycombs. Bees secrete wax from glands on their abdomens to construct these honeycombs.

By storing honey, bees ensure a year-round food supply for the colony, beyond the summer months when flowers are in full bloom.

Honey bees exclusively subsist on pollen and nectar, adopting a herbivorous lifestyle. (Under exceedingly rare circumstances, honey bees may consume their own larvae when faced with severe food scarcity.)

Natural Habitats of Wild Honey Bees

Native to the Old World, honey bees originated from Asia or Africa before spreading across Eurasia.

In the wild, honey bees predominantly inhabit woodlands, establishing their nests within tree cavities.

European settlers transported honey bees to other continents, resulting in their current presence on every continent, with the exception of Antarctica.

Unveiling the Distinct Types of Honey Bees: Queens, Workers & Drones

Colonies of honey bees encompass an impressive population, housing up to 50,000 or even more individuals.

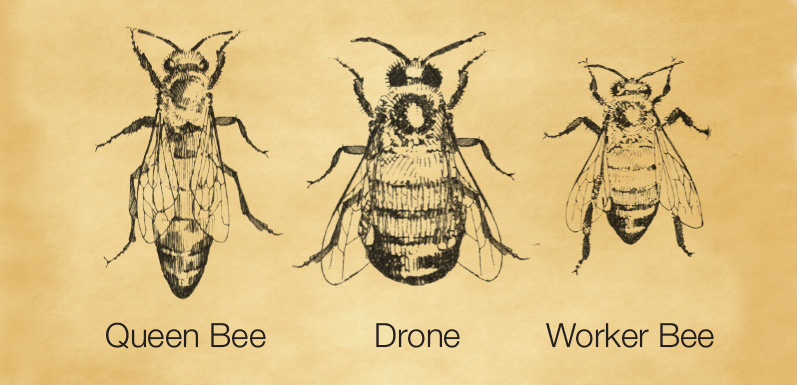

Within each colony, three distinct honey bee types coexist: a solitary queen bee, tens of thousands of worker bees, and several hundred to a few thousand drones, depending on the time of year. Queen bees and workers are exclusively female, while drones represent the male members.

Queen Bee

The primary function of a queen bee revolves around egg-laying. She serves as the mother to the majority, if not all, of the bees inhabiting the colony. Worker bees diligently safeguard her and provide nourishment.

The queen bee releases a unique chemical known as the queen scent or queen mandibular pheromone, signaling her status to other colony members.

Identifying the queen bee proves feasible due to her larger size compared to workers and drones, as well as her elongated and pointed abdomen.

Unlike a worker bee, the queen’s stinger lacks barbs, enabling her to sting multiple times without fatality. Newly emerged queens employ their stingers to eliminate other developing queens.

Queen honey bees boast a lifespan of three to four years.

Worker Bees

Comprising the majority within a colony, worker bees are all female individuals.

Infertile by nature, worker bees do not typically engage in egg-laying. Instead, they assume responsibility for maintaining the colony’s functionality. Their tasks encompass nurturing the young, providing sustenance for the queen and drones, constructing and safeguarding the nest, and foraging for nectar and pollen.

The stingers of worker bees possess barbs. When a worker bee stings a mammal or bird, the stinger and venom sac become lodged in the victim’s flesh, leading to the bee’s demise.

However, if the worker bee’s barb remains unstuck, it can sting multiple times without succumbing. This scenario is more likely to occur when stinging non-mammalian creatures.

Drones

Drones represent the sole male bees within a colony. Like the queen, they receive sustenance from worker bees. Drones exhibit a larger and broader physique compared to workers (though smaller than the queen) and can be identified by their sizeable eyes. (Exceptional visual acuity aids drones in locating and mating with queens during flight.)

Drones do not actively partake in nest maintenance, although they may contribute to temperature regulation. Nonetheless, drones possess a crucial role in passing on the colony’s genetic material through mating with queens from other colonies.

As a bee’s stinger functions as a modified ovipositor, male bees lack stingers and thus cannot sting.

Once a drone has successfully mated with a queen, its life cycle concludes.

The Life Cycle of a Honey Bee

A queen bee deposits her eggs within hexagonal compartments on the honeycomb. As she lays the eggs, she simultaneously fertilizes most of them with stored sperm.

Fertilized eggs develop into female bees, which can manifest as either worker bees or queens. Unfertilized eggs give rise to male drones.

Within three days, the eggs hatch, and the emerging larvae receive nourishment from worker bees.

During the initial stages, all larvae in the nest are provided with a nutrient-rich substance called royal jelly.

After three days, only the potential queens continue to receive royal jelly, while future workers begin consuming honey and pollen.

Following several molting cycles over the course of six additional days, the larvae enter the pupal stage within their cells. Worker bees cap the cells that house pupating bees.

A worker bee remains in a dormant pupal state for approximately two weeks before emerging as an adult, prepared to assume responsibilities such as nest maintenance and safeguarding its fellow inhabitants.

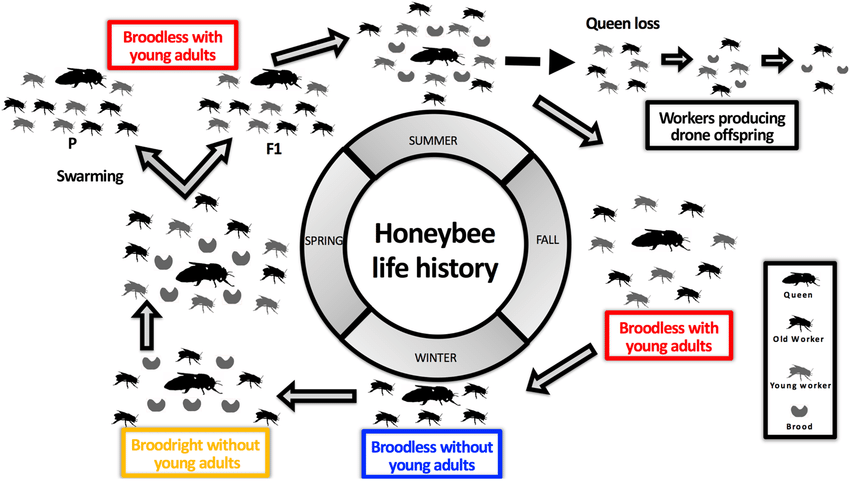

Worker bees are infertile and do not engage in mating. Those born in spring or summer typically live for only a few weeks, while those born later in the year have an extended lifespan, enduring the winter alongside the colony.

Illuminating the Life Cycle of a Honey Bee Colony

Queen bee larvae undergo development within specialized cells within the nest. Once a new queen emerges from her cell, she promptly seeks out and eliminates any other emerging queens or queen larvae within the nest.

Subsequently, the newly emerged queen awaits a warm day to embark on one or more mating flights, during which she mates with males from other colonies.

During this time, the old queen of the colony may have already departed the nest with a group of workers, initiating the establishment of a new colony through a process known as swarming.

Should the old queen not depart with a swarm, the newly mated queen will eliminate her predecessor within two to three days. After mating, the new queen commences egg-laying to initiate the next generation of worker bees within the colony.

Approaching winter, any remaining drones within the nest are expelled by other bees. This expulsion amounts to a death sentence, as without the sustenance and shelter provided by the colony, drones cannot survive.

Throughout winter, the remaining bees huddle together, ensuring warmth while subsisting on the honey diligently produced by the colony during the warmer months.