We’ve all squinted at a bird, saying “what is that?” after discovering hundreds of species of birds in the United States. There are a multitude of choices to make on their own. Being able to distinguish birds is a talent that improves with time and effort, just like any other. Throughout this page, we’ll examine all of the essential aspects to check for when identifying birds and ways to get started.

HOW TO IDENTIFY BIRDS IN YOUR BACKYARD

Color and stripe patterns aren’t the only things that skilled identificationists examine. Those things are critical, but to narrow down your options, there are a slew of additional factors to consider. In order to make an identification, let’s look at the five main types of information we want about a bird.

FIVE BIRD IDENTIFICATION CATEGORIES

- Location & Habitat

- Color

- Shape & Size

- Patterns & Markings

- Movement & Behaviors

One of the most basic but often forgotten ideas is

1. LOCATION & HABITAT

RANGE

Begin by thinking about the condition you’re in and what season it is before you drive yourself insane studying the minute details of the bird. It’s nice to have a range map available when you’re out in the field. They can be found in most field guides and on websites like Cornell’s All About Birds. Knowing when and where certain birds are likely to be found can help you eliminate a large number of them.

A Carolina chickadee may be mistaken for a Black-capped chickadee, for example, unless you have a lot of experience. Nonetheless, since these chickadees have very defined ranges, if you’re in Massachusetts you don’t need to wonder which one you’re seeing. It’s a Black-capped warbler if you live in New England, and a Carolina warbler if you’re in the southeast. Many birds that look a lot alike inhabit distinct regions of the nation and seldom, if ever, cross paths. That’s a good way to eliminate something from consideration.

Because many birds migrate, the time of year you see the bird matters. If a bird is present in your state all year or only appears during spring-summer or autumn-winter, range maps can tell you.

HABITAT

Consider the immediate environment you saw them in once you’ve ruled out birds that are unlikely for your location. Is there a wide open area somewhere? Is there a swamp here? Is it on the beach where you’re going? In a thicket, maybe? You’re probably barking up the wrong tree if you’re certain the bird you spotted was a species of tern but you aren’t near the sea.

When you believe you’ve narrowed it down to a species, like sparrows, but there are several alternative sparrows in your neighborhood and they all look similar, Habitat can be extremely valuable. Each species’ preferred habitat will be highlighted in a field guide.

2. COLOR

When we’re trying to identify a bird, color is undoubtedly the most noticeable thing. It is the first thing our brains catalog for the most of us. In the United States, full body vibrant colors are uncommon. If the bird is completely red or totally blue, it’ll be simple to identify.

Nonetheless, little splashes of color may be a fantastic way to identify birds. Female House Finches and Pine Siskins, for example, are frequently mistaken in backyards. The little streak of yellow siskins have on the edge of their wings and tail is one of the quickest ways to tell them apart, though it’s not the only way.

You’ll be working with shades of gray and brown for the most part. Take note of any little differences you may find in that scenario. Was it a light tan color or a deep chestnut color? Try to figure out the hue. Was there a variation in the color of brown on various parts of the body? If all you perceive is light or darkness, pay attention to that. Which parts of the body were light and which were dark?

3. SHAPE & SIZE

That could fit anything from a sparrow to a hawk if I were to describe a bird with a brown back and white chest with brown streaks. This emphasizes the relevance of size and form.

SIZE

Narrowing down your category might be helped by size. Simple estimations of the sizes of other birds you know can be made if your mystery bird is close to them. However, if the mystery bird is on its own, picture a bird you know well and frequently see. For example, “bigger than a robin” or “smaller than a cardinal,” see how big the mystery bird is in comparison to a bird you are familiar with.

SHAPE

Visualize the birds’ silhouettes while you’re looking at them. The bill’s shape, the tail, the head, the body, and the wings are all worth noting. I’m sure many of you can identify which is an owl, a pelican, a heron, a duck, and an eagle based on the example above.

Birds of the same family typically have similar form. The quicker you’ll be able to narrow things down as you become more skilled at recognizing them.

You may get additional information by combining size and form. In terms of length and width, how long is the birds’ beak? The Hairy woodpecker’s beak is significantly longer in proportion to the width of its head, as compared to the Downy and Hairy woodpeckers. Other items, such as tail length or wing span, can be manipulated using this strategy.

4. PATTERNS & MARKINGS

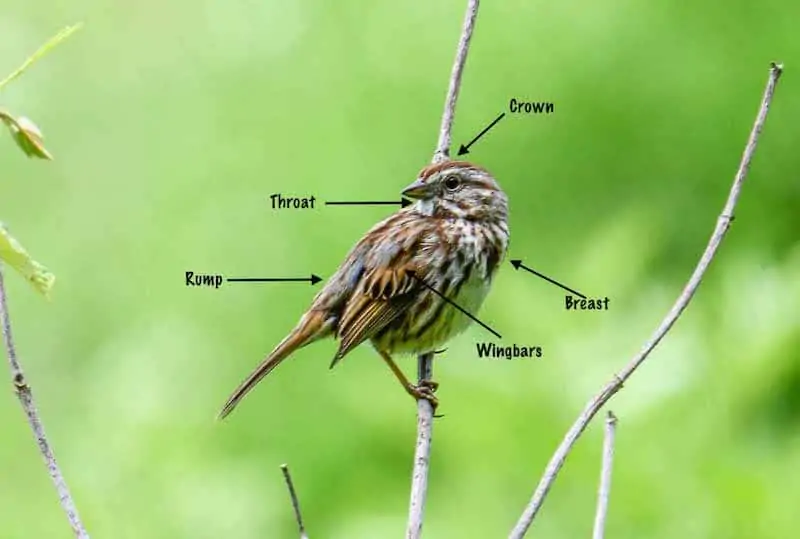

Details make the devil angry. Patterns may be dramatic and obvious at times, but it’s the subtler distinctions that can help you verify your conclusion. Field markings are the term used to describe these patterns, which can be seen in the image below. They occur in different places on a bird and vary in coloration. A colored cheek patch or wingbars are two examples of something that stands out.

It might be helpful to practice identifying common feather designs in different bird species at first. Sparrows are streaked with browns and grays, and members of the thrush family have plain brown backs with white chest markings dotted with brown markings, for example. Most woodpeckers have a black back with white stripes or dots, while sparrows have a black body. You may learn the typical look of distinct groups of birds by observing and flipping through a field guide.

5. MOVEMENT & BEHAVIOR

The way a bird has positioned itself and its “personality” or behavior may often be used by experienced birdwatchers to identify it. After noting size, shape, and other factors, getting a sense of the attitude of each species can really help narrow things down.

Is the bird a calm sitter or is it always on the move? Is it constantly crouching down or making its body more horizontal, or does it hold its body up confidently and upright? Is it constantly hiding in the bushes or will it perch in the open and absorb its surroundings? Over time, through observation, these slight traits of diverse bird species are learned.

HOW DO THEY FORAGE?

Also watch what the bird is doing and where it is going. When it comes to foraging, especially. It’s best to remain hidden in bushes and shrubs. Have you been digging on the ground? Flying back and forth across a field? A tree that zips vertically up and down? Vireos prefer to forage amongst the leaves at the tops of trees, while swallows will dip and dive over large open areas to catch insects in the air. Towhees will scratch around through leaf litter on the ground to find their bugs.

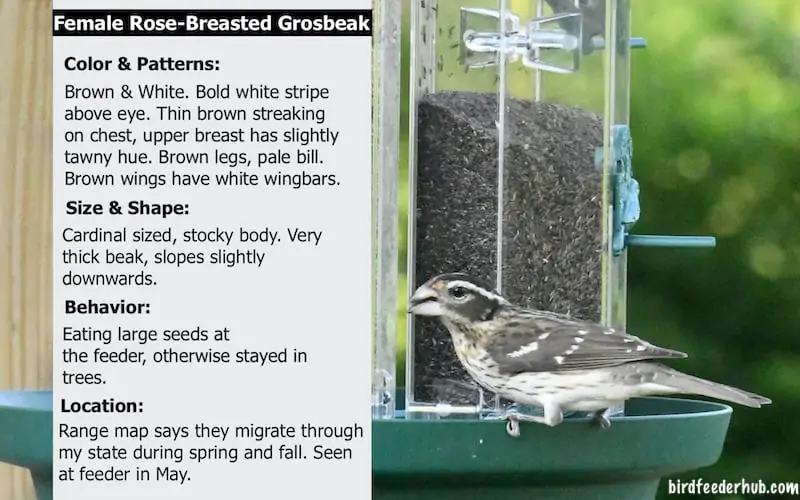

EXAMPLE ID

Here’s how to find a bird at your feeder by using the strategies outlined above.

ADDITIONAL TIPS & RESOURCES

When attempting to determine a bird, here are a few more things to consider, as well as some great guides.

SEXUAL DIMORPHISM

The male of a species and the female have distinct coloration and patterns. Cardinal, blackbird, finch, and oriole females may appear to be quite different than males. The males will be more colorful than the females, as is typical with songbirds and ducks. Consider the birds you frequently observe and research their female equivalent if you notice something new at the feeder and can’t identify it.

Birds may also become duller in the winter, before brightening up during mating season. Many people believe a new bird has arrived at the feeder when the goldfinch’s color changes from bright yellow to washed out olive in the winter.

JUVENILES

A bird’s adult plumage isn’t determined by how big it is when it’s adult. It may take up to a year for juveniles to acquire their full adult coloring and patterns. Your finest estimate will be achieved by using all of the ID tips above, as well as a description or an illustration for birds with complicated juvenile plumage in most field guides.

FIELD GUIDES

If you want to identify birds, I can’t emphasize how essential it is to have a field guide. I like Peterson’s guides, which split up Eastern and Central North America and Western North America into sections. It packs in the most information about the birds in your specific area of the country by sticking to a certain region.

There are, however, a slew of them on the market, and the one that is easiest for you to operate is the one for you. Also, you don’t need the most recent edition of a guide since birds change every year. I’ve discovered that for a few dollars, most commonly utilized bookstores have a couple field guides that are equally good.

Having a real book, in my opinion, is beneficial for understanding the forms, silhouettes, and coloring of birds from specific families. You can actually begin to visually understand those tiny differences that separate flycatchers and vireos when you can compare a complete page of each against each other.

ONLINE RESOURCES

Merlin, a Cornell Lab of Ornithology app that can identify birds on your phone while you’re on the go, is really useful. It asks you a series of questions about the bird you saw, such as what color it was and how big it was, in all of the categories we discussed in this article. After that, it provides you with a list of birds that are frequently seen at your area on the day you saw the bird, if they fit your description. It’s a fantastic resource, even if it doesn’t always identify your bird for you. It helps you focus on the identifying characteristics so that you can identify him/her.